Magnet is a material that has the ability to produce a magnetic field on the outside, which is capable of attracting iron, as well as nickel and cobalt.

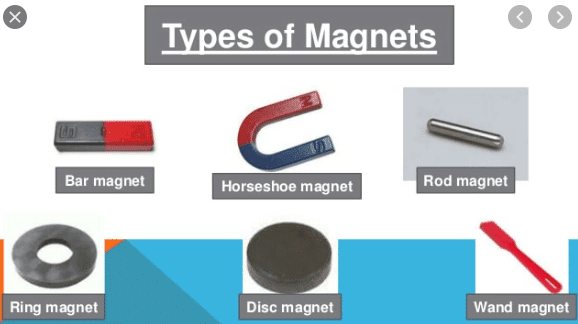

Types of magnet

In addition to natural magnetite or magnet, there are different types of magnets made from different alloys:

- Ceramic or ferrite magnets.

- Alnico magnets.

- Rare earth magnets.

- Flexible magnets.

- Others.

A permanent magnet has a magnetic field surrounding it. A magnetic field can be envisioned to consist of lines of force that radiate from the north pole (N) to the south pole (S) and back to the north pole through the magnetic material.

A permanent magnet, such as the bar magnet has a magnetic field surrounding it that consists of lines of force, or flux lines. For clarity, only a few lines of force. Imagine, however, that many lines surround the magnet in three dimensions. The lines shrink to the smallest possible size and blend together, although they do not touch. This effectively forms a continuous magnetic field surrounding the magnetic.

Attraction and Repulsion of Magnetic Poles:

When unlike poles of two permanent magnets are placed close together, an attractive force is produced by the magnetic field, as indicated. When two like poles are brought close together, they repel each other.

Altering a Magnetic Field:

When a nonmagnetic material such as paper, glass, glass, wood, or plastic is placed in a magnetic field, the lines of force are unaltered. However, when a magnetic material such as iron in a magnetic field, the lines of force tend to change course and pass through the iron rather than through its surrounding air. They do so because the iron provides a magnetic path that is more easily established than that of air. Illustrated this principle. The fact that magnetic lines of force follow a path through iron or other materials is a consideration in the design of shields that prevent stray magnetic fields from affecting sensitive circuits.

How Materials Become Magnetized?

Ferromagnetic materials such as iron, nickel, and cobalt become magnetized when placed in the magnetic field of a magnet. We have all seen a permanent magnet pick up things like paper clips, nails, and iron filings. In these cases, the object becomes magnetized (that is, it actually becomes a magnet itself) under the influence of the permanent magnetic field and becomes attracted to the magnet. When removed from the magnetic field, the object tends to lose its magnetism.

Ferromagnetic materials have minute magnetic domains created within their atomic structure. These domains can be viewed as very small bar magnets with north and south poles. When the material is not exposed to an external magnetic field, the magnetic domains are randomly oriented. When a material is placed in a magnetic field, the domains align themselves. Thus, the object itself effectively becomes a magnet.

Magnetic Properties of Solid

From the study of magnetic fields produced by bar magnets and moving charges, i.e., currents, it is possible to trace the origin of the magnetic properties of the material. It is observed that the field of a long bar magnet is like the field produced by a long solenoid carrying current and the field of the short bar magnet resembles that of a single loop.

This similarity between the fields produced by magnets and currents urges an inquiring mind to think that all magnetic effects may be due to circulating currents (i.e., moving charges); a view first held by Ampere. The idea was not considered very favorably in Ampere’s time because the structure of the atom was not known at that time. Taking into consideration, the internal structure of the atom, discovered thereafter, the Ampere’s view appears to be basically correct.

The magnetism produced by electrons within an atom can arise from two motions. First, each electron orbiting the nucleus behaves like an atomic-sized loop of current that generates a small magnetic field; the situation is similar to the field created by the current loop, each electron possesses a spin that also gives rise to a magnetic field.

The net magnetic created by the electrons within an atom is due to the combined field created by their orbital and spin motions. Since there are a number of electrons in an atom, their current of spins may be so oriented of aligned as to cancel the magnetic effects mutually or strengthen the effects of each other. An atom in which there is a resultant magnetic field behaves like a tiny magnet and is called a magnetic dipole.

The magnetic fields of the atoms are responsible for the magnetic behavior of the substance made up of these atoms. Magnetism is, therefore, due to the spin and orbital motion of the electrons surrounding the nucleus and is thus a property of all substances. It may be mentioned that the charged nucleus itself spins giving rise to a magnetic field.

However, it is much weaker than that of the orbital electrons. Thus the source of magnetism of an atom is the electrons. Accepting this view of magnetism it is concluded that it is impossible to obtain an isolated north pole. The north pole is merely one side of a current loop. The other side will always e present as a south pole and these cannot be separated. This is an experimental reality.

Two cases arise which have to be distinguished. In the first case, the orbits and the spin axes of the electrons in an atom are so oriented that their fields support each other and the atom behaves like a tiny magnet. The substance in which such atoms are called paramagnetic substances. In the second type of atoms, there is no resultant field as the magnetic fields produced by both orbital and spin motions of the electrons might add up to zero. These are called diamagnetic substances, for example, the atoms of water, copper, bismuth, and antimony.

However, there are some solid substances e.g., Fe, Co, Ni, Chromium dioxide, and Alnico (an iron aluminum – nickel-cobalt alloy) in which the atoms cooperate with each other in such a way as to exhibit a strong magnetic effect. They are called ferromagnetic substances. Ferromagnetic materials are of great interest to electrical engineers.

Recent studies of ferromagnetism have shown that there exists in ferromagnetic substance small regions called ‘Domains’. The domains are of the microscopic size of the order of millimeters or less but large enough to contain 1012 to 1016 atoms. With each domain, the magnetic fields of all the spinning electrons are parallel to one another i.e., each domain is magnetized to saturation.

Each domain behaves like a small magnet with its own north and south poles. In unmagnetized iron, the domains are oriented in a disorderly fashion so that the net magnetic effect of a sizeable specimen is zero, When the specimen is placed in an external magnetic field as that of a solenoid, the domains line up the parallel of lines of the external magnetic field and the entire specimen becomes saturated. The combination of a solenoid and a specimen of iron inside it thus makes a powerful magnet and it is called an electromagnet.

Iron is a soft magnetic material. Its domains are easily oriented on applying as an external field and also readily return to random positions when the field is removed. This is desirable in an electromagnet and also in transformers. Domains in steel, on the other hand, are not so easily oriented to order. They require very strong external fields, but ones oriented, retain the alignment. Thus steel makes a good and another such material is a special alloy Alnico V.

Finally, it must be mentioned that thermal variations tend to disturb the orderliness of the domains. Ferromagnetic materials preserve orderliness at ordinary temperatures. When heated, they begin to lose their orderliness due to the increased thermal motion. This process begins to occur at a particular temperature (different for different materials) called Curie temperature. Above the Curie, temperature iron is pare-magnetic but not ferromagnetic. The Curie temperature for iron is about 750°C.

Types of the magnet (video)